All this was reinforced by paperbacks’ already somewhat tawdry and unsavory reputation [1]. It was no accident then that the vintage cover art style reached its definitive expression with the hardboiled mystery story in the late forties and early fifties. Altogether it was the perfect merging of form and content [2], as Lee Server points out in his broad brushstroke characterization of vintage paperback art which emphasizes the noirish and hardboiled elements :

. . . . . garish oils on canvas, a dreamlike exaggerated realism, the depicted scene an overheated, pheromone-charged moment from the enclosed narrative. With their typically lurid hues and tawdry views of urban modern life, the covers looked like freeze frames from some lost B-movie. Reflecting the most frequent subject matter of the paperback novel in this era, the illustrations offered endless variations on recurring motifs, namely crimson lipped females in lingerie, granite jawed tough guys, blazing .45s, rumpled bedsheets, neon-lit hotel rooms, a blue-gray haze of cigarette smoke, alleyways and streetcorners at permanent midnight [3].

Bonn provides an even more succinct - if less precise - description : “the dominant style of color illustrations at this time was a brooding realism to which a thick veneer of sex and sadism was imposed.” [4] But for pithy conciseness the prize must certainly go to the ultra-conservative Alan Lane, founder and publisher of Penguin Books, who dismissed the American style as “bosoms and bottoms.” [5]

No discussion would be complete, however, without considering the significance of the target audience, which was, generally speaking, male, heterosexual, 21-50 years old, urban/suburban, middle- and lower middle-class, and mildly well educated. Or phrased another way, WWII GIs who had just returned home. These guys had gotten a taste for this sort of thing - albeit of less colorful subject matter - during the war with government supplied Armed Services Editions paperbacks [6]. With the war now over, their reading tastes demanded stronger stuff than the standard classics, nonfiction, and British cozies of the early paperback era.

[1] “Hardboiled paperbacks of the 1940s can be frightening objects. They are abject, gaudy, dirty-looking and strangely alive. They needed to be stopped, but even Congress could not do it, although they tried.” (Margaret Meriçli, Broken Hallelujah: The Cultural Significance of American Hardboiled Fiction in Paperback, 1940-1955).

[2] The vintage cover style extended to other types of fiction* besides hardboiled mysteries, including the usual suspects of Sci-Fi, Fantasy, Westerns, Spy/Adventure, Romances, and British mysteries, but also new genres which appeared in the early 1950s,** whose shocking subject matter seemed ready made for the exotic, unsavory world of paperback fiction: juvenile delinquency; drug addiction***; homosexuality; backwoods nymphomania; the Beat poets; racism, to cite but a few. Not so surprisingly, these offbeat, quasi-forbidden genres are among the most highly prized by collectors today.

* Even the most ‘respectable’ authors weren’t exempt from the sensationalist treatment, Steinbeck’s To a God Unknown and the afore-referenced Nana being two of the more notorious examples. See also : Richard Hoffstedt, “Steamy Steinbeck : Paperbacks : 1947 – 1957,” Steinbeck Review v3 n1, Spring 2006, pp. 118-128.

** A new publishing trend of the 1950s, the movie tie-in, wasn’t exactly a genre, or new, for that matter, as the first ones had appeared around 1940. But nonetheless the tie-in paperback hit its stride in the 1950s and reflected the industry’s desire for fresh material and packaging.

*** For more on the ‘dope menace’ paperbacks, see : Bill Ott, “Confessions of a Pulp Junkie,” Booklist, v105, n5 (Nov 1, 2008), p 80.

[3] Server, Over My Dead Body, pp. 57-58.

[4] Bonn, UnderCover, pp. 55-56.

[5] Very much a creature of old-school British sensibilities, Lane stubbornly resisted any movement toward the excesses of the American vintage style; both the British and American lines of Penguin Books retained a basic conservatism with highbrow literary material and rather abstract and restrained – if indeed often stylish – cover art. (Alan Powers, Front Cover : Great Book Jackets and Cover Design, London, Mitchell Beazley, 2001, pp. 58-59).

[6] Christopher P. Loss, “Reading Between Enemy Lines : Armed Services Editions and World War II,” Journal of Military History v67, n3 : 811-34.

Christie, Agatha. Evil Under the Sun. N.Y.: Pocket Books, 1957. #2285. 6th printing. James Meese delivers another gorgeous design for the late fifties Pocket reissue of Evil Under the Sun. The cover is especially noteworthy for its nice balance of the various hues of orange, yellow and red. Is it just me, or did Meese use the same model again & again -- compare the woman on the present cover with that of the above-cited Ann Avery or the Flickr collection of Meese covers.

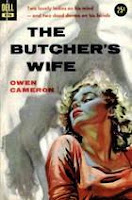

Cameron, Owen. The Butcher’s Wife. N.Y. : Dell Books, 1954. # 896. Cover art : William Rose. "Two lovely ladies on his mind, and two dead dames on his hands." – front cover. I confess to not being familiar with author Cameron or cover artist William Rose. However, Rose’s cover for the book is a knockout. The woman in the foreground is rendered in exquisite detail featuring peach and off-orange tints for her dress [which is nicely matched in the lettering], along with a pouting mouth and a defiant upturn of the head. The shadows in the background of a man carrying a [presumably] naked, dead woman, help to conjure up a sinister, macabre atmosphere.

Williams, Tennessee. The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone. New York : Signet Books, 1952. #955. Cover art : James Avati. Another brilliant Avati cover, with much psychological insight into the character despite the artist’s rather subtle style and technique. Mrs. Stone dominates the front cover, glancing warily at the man on the left. The sketchily rendered figures in the background suggest a rather undefined menace.

Hughes, Dorothy. The Candy Kid. N. Y. : Pocket Books, 1951. #845. First printing. Gloriously lurid, un-pc cover art by Edward Vebell from Pocket’s most melodramatic years : a rather elegantly dressed tough guy chokes a woman as she grabs his hair trying to stop him. Great use of bright red and yellow on both front and back covers. The Candy Kid is a thriller set near the Mexican border by sometime New Mexico resident Dorothy Hughes.

Gardner, Erle Stanley. The Case of the Borrowed Brunette. N. Y. : Pocket Cardinal, 1959. #C-380. First printing, November 1959. Cover by ’Charles’. The covers for the Erle Stanley Gardner mysteries are a virtual catalog of changing vintage paperback styles & techniques. Charles’ rendition of a languorous brunette, presumably the title character, reclining on a pillow, is a classic late fifties image of beauty : sleek, sophisticated, well-coiffured, no-nonsense.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment